Today I will be concluding my series on water pumps with the India Mark pump and the EMAS Flexi-Pump. One of these pumps, the India Mark, has been widely used in developing countries for decades and continues to be improved on (there is the Mark II and Mark III). The EMAS Flexi-Pump has a simpler design and is easy to make on your own. Let’s get started.

The India Mark Pump

The India Mark II was designed during the 1970’s in response to the lack of reliable hand pumps in rural areas of India (there is no Mark I). At that time most people were using cast-iron hand pumps, and actually over-using them, leading to their breakdown. In 1974 UNICEF carried out a survey in India and found that 75% of these cast-iron pumps were non-operational. This caused a bit of panic, and led to UNICEF partnering with two Government of India organizations to begin developing a more reliable hand pump.

In developing this hand pump they had several goals. One was to develop a hand pump that was sturdy and could last at least one year without needing repair. Now, to me one year doesn’t sound like a lot, and it’s not, but they needed to set a benchmark, and at the time one year was much better than what other pumps could promise. They also wanted this pump to be able to be manufactured locally, including using locally available material and components, and have it be available at a low cost (less than $200 US). Further, they wanted the pump to be user friendly and to be able to pump with minimal effort. This was due to the fact that women usually are the ones who collect water for their family. Finally, they wanted the pump to be standardized which they believed would lead to a better maintenance system, and overall more reliability.

One thing that is amazing about the development of this pump is that all of the players involved, UNICEF, MERADO, and Richardson & Cruddas, worked on development just because they knew that it was something that the rural people of India desperately needed. There was never any contract between UNICEF and either of the other two parties. They were all just working together for the greater good, something that is very rare. Further, they all agreed that once their goals were met and the pump was developed its design would become public domain, meaning anyone could gain access to the specifications and build one themselves if they had the means. Amazing!

By the end of 1977 they had field-tested the Mark II, with overwhelming success, and it was put into production. During 1978, 600 pumps were being manufactured per month. By 1982, 100,000 pumps had been manufactured, and by 1984 200,000 pumps were being manufactured annually. All of this adds up to four million Mark II pumps having been installed in India by 2010, and they have also been installed in many other Asian countries as well as in a number of African countries (over five million produced in total). That’s a lot of water for a lot of people!

Although the Mark II was a huge success they wanted to make it easier to maintain, and that led to the Mark III. The improvements made included redesign so that the piston and foot valve could be removed without having to remove the rising main, a change that made maintenance much easier. Actually, a study found that repairs to the Mark III took 67% less time than for the Mark II. This is great, but this change came at an increase in the cost and a limit of 30 meters being put on the depth the pump could be installed to. Studies afterward found that making the pump maintenance easier didn’t necessarily make it more desirable. It found that if people at the community level were able to fix the Mark III they could also fix the Mark II, and therefore, the rise in cost for the Mark III made it less desirable than the Mark II (not to mention that the Mark III was no more reliable than the Mark II). This study also found that maintenance cost did not come down with the introduction of the Mark III. However, even though the Mark III wasn’t as big of a hit as the Mark II, it still has everything that the Mark II had which means it’s still a great pump. Enough of the history, how does the pump work?

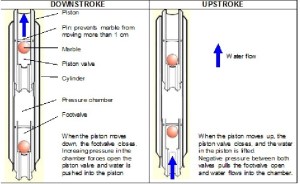

The India Mark pump is a conventional lever action hand pump (also known as a reciprocating hand pump). Here’s a very basic description of how it works: starting at the top of the pump, you have a pump handle that is connected to the pump rod. The pump rod extends down the rising main and into a cylinder, where it has a piston on the end. At the bottom of the cylinder there is a foot valve. When the handle is pumped the piston moves up and down. On the up-stroke the piston creates pull and the foot valve opens and allows water into the cylinder. Then on the down-stroke the pressure created by the piston closes the foot valve and forces the water through the piston and up the rising main. For those of you like me that would rather see a picture, here you go (click to enlarge):

What can the India Mark do? It provides water from a depth of up to 50 meters (30 meters for the Mark III) which makes it a deepwell hand pump. It will serve a community of up to 300 people, and provides anywhere from 0.8 m3 to 1.8 m3 per hour depending on the depth of the well.

Being the most widely used hand pump in the world has also led to there being thousands of India Mark pumps left broken-down and abandoned throughout the world. Everything needs maintenance at one time or another, and because there wasn’t a good maintenance system set up once it was required the pumps were often abandoned. However, I don’t believe this should be taken as a reflection on the pump itself, and instead it should be taken as an oversight on the part of the people who installed the pump.

I really don’t know how I feel about the India Mark II/III. The India Mark pump is sturdy and tough (although not corrosive resistant) which is a good thing if it’s getting used a lot, however, they still break down. And if you don’t know how to fix it, or there’s no one in the area, then once it needs to be repaired the users will again be without water. For the India Mark to be sustainable there needs to be a system set up for regular maintenance, or at least someone in the immediate vicinity needs to be trained on how to repair the pump. But then you still have the problem of spare parts. If there’s a shop that can make them then it’s not a problem. If there’s not then it doesn’t really matter if someone knows how to repair the pump because they won’t have the means to do it. That’s why I think having a community repair shop with spare parts and the knowledge to fix the pump is the best answer. Without something like this in place people will have water, and be thankful for it, for one to three years and then back to searching for something to drink.

I should also note that while doing research on the India Mark I am consistently reading that without proper quality control the pumps will not be as reliable. There are certain manufacturers that are approved by the Government of India to manufacture the India Mark because they have been certified and comply with strict quality control guidelines. This means there’s probably a lot of fake/low-quality India Mark pumps out there, so if you’re going to buy one be careful and make sure it was made by an approved manufacturer.

* * *

EMAS Flexi-Pump

The second pump I’ll be looking at today is the EMAS Flexi-pump. This pump was developed in Bolivia and was first put to use in Honduras in the mid-1990’s. For the most part it has stayed in South America, with about 30,000 installed in Bolivia, Honduras, Peru, Ecuador, Nicaragua, and Brazil. However, it has also been introduced in South-East Asian.

The EMAS Flexi-pump is a direct action pump, and can be used for irrigation or for drinking water. I like this pump because it is very simple and made with materials that can be found in most places. It is made of plastic and galvanized piping, a piston and a foot valve that are made from a glass ball (marble), a metal pipe and T-fitting for the handle, and a discharge nipple. You need two difference sizes of plastic piping to make this pump.

A simple description of how it works is the smaller size pipe is placed inside of the larger pipe. The inner pipe is connected to the handle and moves up and down, while the larger (outer) pipe stays in place. When the inner pipe is pushed down the piston valve opens, the foot valve closes, and water flows into the pipe. Then on the up-stroke the piston valve closes and the foot valve opens, allowing more water into the larger pipe. Then on the next down stroke the water already in the pipe is pushed out of the outlet in the handle. A hose can be attached to the outlet valve and water can be pumped up to 300 meters. Very simple. Here’s two drawings showing the parts of this pump and illustrating how it works:

Because of the up and down pumping action required for this pump it is not as comfortable to pump over long periods of time as a lever-action hand pump. Also, because it is partially made of plastic piping is it not as tough as a pump made entirely out of metal. Other than these two points there really isn’t anything bad about this pump.

It can pump from up to a depth of 40-50 meters; at 10 meters it can pump up to 30 l/min which is enough to serve up to 50 people. As far as cost, the best figure I have seen is $5 US plus $1 US for each meter of depth, so for a 20 meter deep well it would cost $25 US (excluding the cost for the well or borehole). Because this pump is simple and can be constructed by the people that will be using it they will also be able to maintain it, making the EMAS Flexi-pump very sustainable. There are also ways to modify this pump so that it can be pumped by a windmill, a children’s seesaw, or other similar types of technology. Finally, this pump can fit boreholes as narrow as 1.25 inches. This is important to note because a borehole this small is fairly low-cost but can provide much needed water.

Overall, I think this is a great water pump for rural areas. It’s low-cost, uses materials that are available in most places, has a simple design and therefore can be built and maintained by the people using it, and it can pump from great depths. That’s my kind of pump!

* * *

I started this series on hand-pumps in order to 1) introduce people to different types of hand-pumps and how they are built and operated, and 2) to start a discussion on the pros and cons of different types of pumps. I reviewed six pumps in total; the Rope pump, No. 6 pump, the Treadle pump, Malda pump, and now the India Mark and the EMAS Flexi-pump. If you missed the earlier articles you can find them here: Part 1, Part 2. I picked these pumps with the hope of giving an even balance between very simple pumps that can be built by most people with a little technical knowledge, and more advanced pumps that require someone trained in their operation and maintenance. There are also many other options for pumps.

If you’re a regular reader of this blog you will know that I am a huge fan of simple, appropriate technologies, and therefore I’m more inclined to support those types of pumps. This is mainly because of the problem with maintaining a more technologically advanced hand-pump (as well as higher cost). However, if the means are there to buy and be able to maintain a more advanced pump they can be more beneficial in certain situations.

There is no “best” hand-pump. Each situation is different and has to be looked at to figure out which pump is best for that situation. You have to look at required output, pumping depth, cost, location of the pump in relation to availability of spare parts and maintenance, etc. Hopefully this series has been helpful and educational. I’d love to hear about your experience with any of these hand-pumps, and/or what you thought of the articles, so please leave a comment. Also, please share this with anyone you think would enjoy it. Below there are some great resources to help you understand as well as build your own pumps. Thanks for reading!

Resources:

Installation and Maintenance Manual for India Mark II Handpump

India Mark Handpump Specifications

Build-an-EMAS-pump by Paul Cloesen

Sources:

How Three Handpumps Revolutionized Rural Water Supplies

Field Guide to Environmental Engineering for Development Workers, by J. Mihelcic, L. Fry, E. Myre, L. Phillips, and B. Barkdoll

WaterAid Technical Brief: Handpumps

Build-an-EMAS-pump by Paul Cloesen

very well presented

The article is very informative.

Some additional further reading on EMAS: https://www.rural-water-supply.net/en/resources/details/518

This was authored by my colleagues and my thesis ad adviser. My MS thesis is centered on the EMAS pump and we will have more research published on it in the coming months.

Thanks for sharing the document Jake

Great resource, thanks!

I was recently in cambodia on a mission trip. I would like to learn more about how my organization can provide wells for fresh water. i.e. water tables drilling requirements well heads etc. can you help me?

Hi John,

I could try. If you send me some specific questions I’ll see what i can do.

Thanks!

Very nice and informative post. I learn lots of things from here. Thanks a lot for sharing.